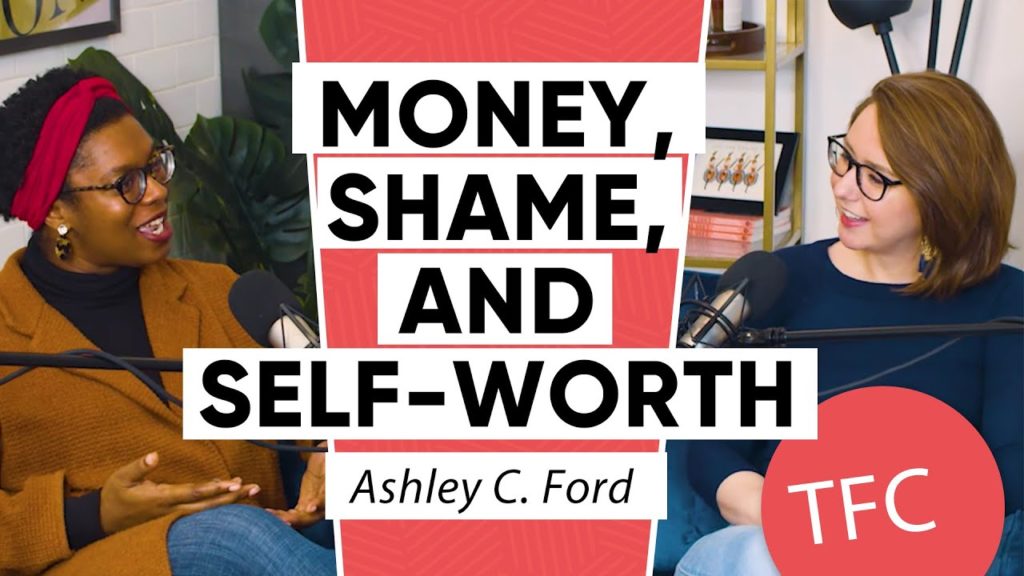

Ashley C. Ford On Growing Up Low-Income & The Privilege Of A Second Chance

Each week on our new podcast series, The Financial Confessions, we’ll be sitting down with a new guest to talk all things money, getting ahead in your career, and the financial insecurities that make us tick. In this episode, Chelsea spoke with writer Ashley C. Ford. Read on for their conversation about growing up low income, and how money played a part in their relationships with their parents. Listen to the full episode here or scroll down for the full video!

Chelsea: I’ll never forget the day of my 18th birthday when I got control of my savings account. I went to the bank, I took all of it out, and I spent all of it within a matter of weeks. And it was probably– I can’t remember exactly how much he was– but I think I was like $12,000.

Wow.

Yeah. It was drained. It was completely drained. It’s funny, because my parents were furious at me, which I would be too if that were my child. They were absolutely furious at me. They were disgusted with me, and I think rightfully so. Because that money was spent in the most frivolous, stupid, inexcusable ways.

But looking back, I have empathy for myself, because I feel like I — and I’m not saying this was rational. Because to your earlier point, there are many people who grew up in way worse circumstances than I did. And as you mentioned earlier, I think before we were talking, that poverty is not a competition. And so I never want to make it sound like I was in such a bad situation, because I wasn’t.

But I definitely got from my experience growing up, a feeling. An almost frantic sort of furtive relationship around money that was out of my control. And I look back and I say, someone who would have done that on her 18th birthday — yes, it’s immature, yes, impulsive — but it’s also mentally unwell. That is someone who has a completely unwell relationship to money, and who has no idea what to do with it, and can only experience it as temporary serotonin hits.

My parents were totally right to be extremely upset with me. They have every right. But I also feel, like looking, back I forgive myself for having done that. And I at the very least, even if I still say that was a terrible thing to do, I understand why I did it. And in understanding why I did it, I can start to say as an adult, you now do have those choices to make. And it’s up to you to say, is this thing a meaningful purchase for my life, or am I just thrilled at the ability to purchase it? Which often feel the same on first blush.

They absolutely feel the same. And I think that that’s where a certain kind of privilege comes in. And I think that while privilege works in hierarchies– these people have this much privilege, these people have this much privilege– but everybody got a little bit. You know what I mean? The biggest privilege is the privilege of a second chance.

Oh absolutely.

That is the biggest privilege. And I think that’s something that people who have never dealt with a certain kind of financial instability, that’s what they really don’t understand. Is that it’s not about whether or not people make mistakes, because everybody makes mistakes. Everybody’s going to make mistakes, everybody has made mistakes. The people who are telling you, don’t do this. The people who are telling you that when you were five and six and 10 and drilling that into your head before you were out on your own, are usually telling you that because they made their own mistakes. The difference between those people and someone who has to sleep outside, in a lot of cases, is the privilege of a second chance.

Absolutely. The ability to have your mistakes be lessons and not punishments. And being able to learn from a mistake is such a privilege. And I definitely had that privilege. I was living with my parents when I spent that money. So even though I felt the pain of it in superficial ways, I wasn’t on the street because of it. So I’m very cognizant that a lot of people don’t have that privilege.

But it’s interesting, because we were talking earlier before filming, about how the way we sometimes talk about our upbringings will upset our parents. My mother, even a couple of weeks ago, she was at my house and she was crying. And she was like, I hear you talking sometimes about how you wanted for this, or you felt insecure or upset about that. And it breaks my heart as I always felt like we had enough. And it’s heartbreaking because we did have enough. I was never hungry, I was never worried about, would we have a place to live tomorrow. And we owned a house in a very not ritzy neighborhood of Charlotte, North Carolina, but we owned a house. And for them, that felt like that was such an achievement, and that was such a thing to be proud of. And they did raise two daughters, and they did make it, and they have ascended in class strata now.

But I always tell her, I’m like, you’re right, but so am I. We can both have an experience and a relationship to this. And to be honest about what that felt like is in no way an attempt to denigrate what you did, because I’m so proud of what you did. But it also is something that I don’t think it’s fair that you guys had to live the way that you had to live. I want better for you, and I want better for that 30 year ago version of you.

Yes. This is what it’s so hard sometimes to get across to my mother. Now my dad is a completely other story. My dad is pretty much like, yeah, you’re right. My dad is very much like, you own your feelings. Yep. Because my dad messed up in a major, major way. Life defining.

How so?

My dad went to prison when I was around six months old. And he did not get out until about a month before I turned 30.

I remember reading a lot about your experience with having an incarcerated parent. And I do want to talk about the financial realities of that. But I am curious what you have a hard time explaining to your mother.

I have a really hard time explaining to her that I feel like what she did was miraculous. My mom raised four kids by herself. No consistent help, never a dual income in our home ever. She raised four kids by herself. She worked constantly. Like really as much as she could. My mom took all available overtime, everything.

What did she do for work?

My mom worked at the sheriff’s department in our county. She was essentially like a guard at the jail. My mom’s terrifying. She is. She’s the best. You’d meet her and you’d be like, oh, she’s really sweet and charming. Also I would never mess with her in my life. I don’t know what it is about my mom, she’s just got this terrifying thing. And she was a perfect —

That’s aspirational.

— county jail guard. Because everybody loved her and/or was scared of her. But I think what she did was miraculous. It does not change the fact that she never had enough. And not even that she never had enough in terms of money, but also she never had enough in terms of options. It’s not just about what you were able to do, it’s about what was available to you. That’s the tragedy. That’s the part that’s a tragedy. Because there’s nothing more she really could have done in terms of work and providing.

Really. There was nothing more she could have done. I can’t imagine what my mother’s options would have been. Go back to school? How?

That costs money.

That costs money. That costs money. It takes away money, and it takes away time.

Which is money.

Exactly. Her options were so few, and so much of that didn’t have anything to do with what she chose. It had so much to do with the circumstances of her life. And I think she wanted to erase that for me, or she wanted it to not be a factor for me by denying it in herself. Which of course doesn’t work.

And so now that I’m talking about these things and I’m having this conversation publicly, a big part of my tension with my mom around that is her still holding on to this image, and wanting to have this image more than she wants to heal what happened in reality. And it’s hard for me because I’m like, I just want you to be here in reality with me. I want you to come over here to reality with me, not because you’re saying these things didn’t happen, but because you are really attached to the idea that it doesn’t count that we lived in poverty if it never looked to other people outside our home like we were living in poverty.

Like this story? Follow The Financial Diet on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter for daily tips and inspiration, and sign up for our email newsletter here.